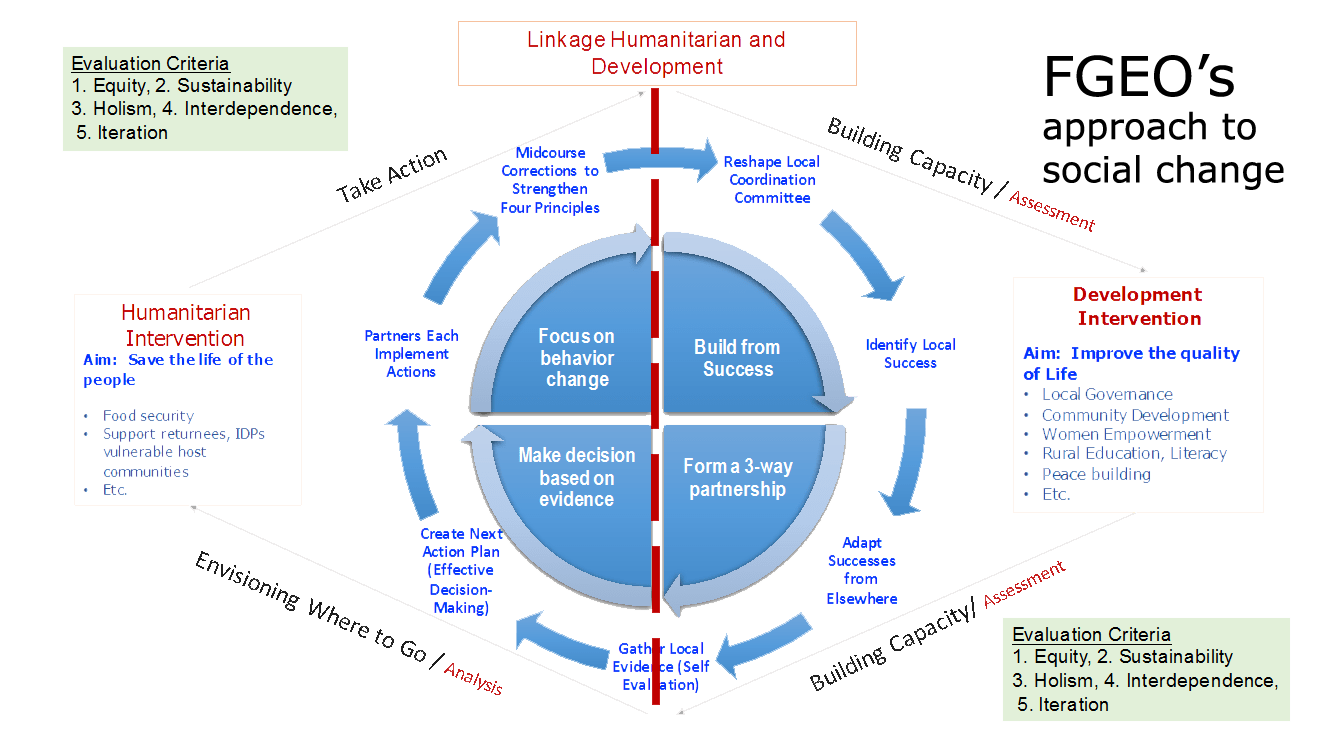

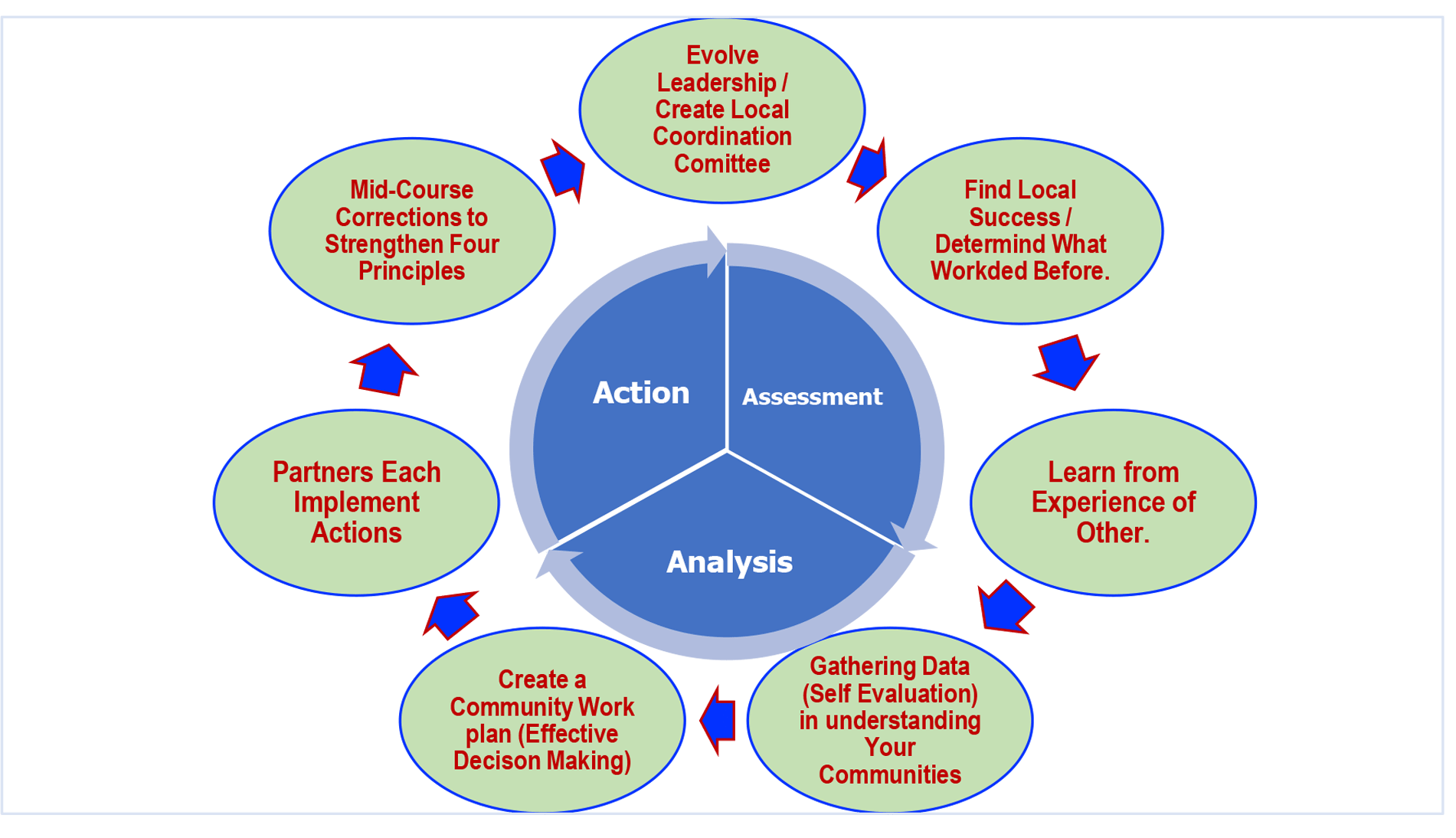

FGEO's Approach to Self-sufficiency and Social Change

FG has a history of self-reliance and community empowerment that is based on a participatory

and

inclusive decision-making processes; gender equality, transparency and accountability and

sustainability. It has used its proven approach (SEED-SCALE) in its target areas in

Afghanistan. SEED is

an acronym for Systems of Self Evaluation for Effective Decision-making. The focus of

activities from

the beginning is to facilitate sustainable community based, community owned socio-economic

and systemic

change in resource-poor settings. Rapid expansion occurs with systematic promotion of

training and

support with ideas but with minimum outside funding to build self-reliance, community

capacity, changes

in behavior and social norms and community empowerment. The SCALE is an acronym for Systems

for

Communities to Adapt, Learn and Expand in rapid extension from successful local sites, then

transforming

the best successes into Learning Centers, which extend to new regions to form a network of

Learning

Centers for national coverage. The SEED-SCALE is the FGEO Framework for action that allows

communities to

analyse their conditions in relation to national dynamics, take appropriate actions based on

their

priorities and resources and lasting change.

FGEO specializes in a partnership-based approach that strengthens linkages and skills among

communities

(bottom-up human energy), government (top-down enabling policies and financing), and

non-governmental

organizations (outside-in technical support) to address the needs of people living on the

margins of

society and protect fragile ecosystems. The core of FGEO's work is a system that communities

and

governments can use to shape their futures. In its entire project portfolio, FGEO stresses

the importance

for self-reliance and empowerment of local communities. The institution’s intention is to

create the

attitudinal and behavior changes that will improve the lives and livelihoods of community

people. In our

approach, efforts to instill in all activities a “You can do it” set of convictions builds

capacity in

our entire target areas.

It is common these days to speak of methodologies of self-reliance and empowerment – almost

all

organizations in the world claim to do or at least promote these. But most organizations

attempt

self-reliance and empowerment by giving services. Self-reliance is not giving to, but rather

it is

building out from people. Future Generations has an exemplary world-encircling evidence base

of

achieving both self-reliance and empowerment. Distinctive about the Future Generations

approach is that

it is based on scholarship begun with funding from UNICEF in 1992, which continues today.

The

methodology that has been developed is known as SEED-SCALE that the process was first

presented in two

monographs at the 1995 United Nations Summit in Copenhagen and more recently articulated in

the book

Just and Lasting Change: When Communities Own Their Futures. It continues to be refined

through ongoing

research, collaboration, and field application.

FGEO implements SEED-SCALE theory of change that offers a process for each community to

develop its own

services and enhance its efficacy and control. The approach uses resources all communities

have, and

builds from actions that have already started. The SEED-SCALE process activates the energy

and resources

of communities (SEED) and expands successes across large regions through government

partnership (SCALE).

SEED-SCALE is a framework to understand how to enable community empowerment as well as

methodology

(complete with guiding principles, action steps, and evaluation criteria) that can be taught

to and used

by communities functioning at the most basic level.

The essence of SEED-SCALE approach is the recognition that community members are the primary

authors and

actors for addressing their socio-economic problems, and awakening them to a possibility for

a better

life and self-reliant actions. FGEO will ensure its humanitarian and development programs

with

communities are:

Targeted the most vulnerable – for their Self-sufficiency that is the ability to provide

everything one

needs in sufficient quantities to save life and livelihoods.

Dynamically Transformative - community members uncover their own definition of human

well-being and the

direction they themselves define as most desirable to ensure it. This shifthelps them to

move away from

dependencies.

Empowering - communities through participatory planning, implementation, and management of

local

development activities.

Improving – local leadership will be strengthening to become more accountable and inclusive.

Connected – although arising as local initiatives, strong linkages and partnership are

forged with

regional and national development actions.

Iterative – so community initiated success leads to another and then to another until

community networks

are established district wide, regionally and nationally.

In all its humanitarian and development works with communities, FGEO will not present itself

as a source

of funding, but as a facilitating partner and capacity builder. The SEED-SCALE approach has

enabled the

FGA to focus communities on how they themselves can channel their social and human capitals

towards

overcoming socio-economic problems rather than always looking for outside sources of support

and

funding. This means the work of FGA promotes self-sufficiency in the emergency or

humanitarian situation

and moves toward self-reliance and empowerment.